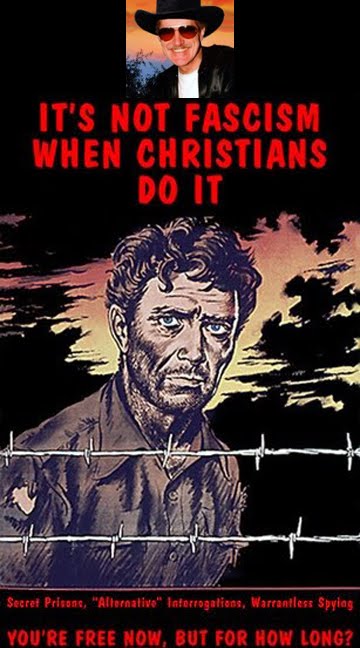

Torture, Genocide, War Crimes, Wikileaks, Trump Trumped, CIA/DOD Shift Immigration Legislation And Other Convoluted News And Events Of The Day

A respected, mainstream theologian is seriously arguing that as long as God gives the thumbs-up, it's okay to kill pretty much anybody.

OBAMA TO SHAKE UP SECURITY TEAM, PANETTA TO PENTAGON WASHINGTON | (Reuters) - President Barack Obama will name Leon Panetta, a veteran Washington politician and current CIA director, as his Defense Secretary as he resets his national security team ahead of the 2012 presidential campaign and a battle over the Pentagon budget. U.S. officials also said on Wednesday that Obama would nominate General David Petraeus, who is running the war in Afghanistan after leading the campaign to quash insurgency in Iraq, to replace Panetta at the CIA. Trouble-shooting diplomat Ryan Crocker, who previously served as ambassador to Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, Kuwait and Lebanon, will be named as ambassador to Afghanistan. The changes are expected to be announced on Thursday. The long-anticipated overhaul could have broad implications for the Obama administration, which is pursuing deeper defense spending cuts in the face of a yawning budget deficit and will start withdrawing troops from Afghanistan this July. Panetta is a Democratic party insider seen as close to Obama who could be more receptive to deeper defense spending cuts than outgoing Defense Secretary Robert Gates, a holdover from the Bush administration. Panetta, who turns 73 in June, is a former U.S. representative from California who was chairman of the House Budget Committee. He was former President Bill Clinton's budget director, then chief of staff. As well as starting the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the United States is set to pull U.S. forces out entirely from Iraq by the end of 2011, while the future course of its campaign in Libya remains unclear. The White House declined comment on the expected changes, as did the Pentagon. White House spokesman Jay Carney said only that "we'll have a personnel announcement for you tomorrow." Gates' clout among Republicans helped shield Obama from early criticism of his handling of war policy, a political asset that the president will be hard pressed to duplicate as he heads into the 2012 presidential campaign. Officials said on Wednesday Petraeus had left Afghanistan and was on his way to Washington and was expected to arrive before the White House's Thursday announcement. By choosing Petraeus, the commander of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan, Obama advances perhaps the U.S. military's most famous general and a hero among Republicans to one of the most important and difficult posts to fill in his administration. Petraeus, 58, is credited with pulling Iraq from the brink of civil war after the 2003 U.S. invasion before he assumed command of U.S. and NATO forces in Afghanistan. Before word of the reshuffle broke, some Washington insiders suggested the White House wanted a high-profile position for Petraeus to ensure he would not be tapped by Republicans to challenge Obama next year, perhaps as a vice-presidential choice. One U.S. official said Lieutenant General John Allen, deputy commander of U.S. Central Command, would succeed Petraeus as head of the Afghanistan campaign. (Reporting by Mark Hosenball, Steve Holland, David Morgan and Phil Stewart; Editing by David Storey) |

Jared Rader/The Daily : Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Israel committed war crimes during its 2008-09 assault on the Gaza Strip in Palestine, including targeting civilians, a prominent Israeli policy critic told an audience Tuesday in the Oklahoma Memorial Union’s Meacham Auditorium.

Norman Finkelstein, author of several books on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and former DePaul University professor, spoke about the conflict in light of recent retractions made by the leader of a UN fact-finding mission April 1, which cleared Israel of targeting civilians.

Roughly 1,400 Palestinians were killed during the 22-day assault, most of whom were civilians, according to various reports. On the Israeli side, 13 were killed, three of whom were civilians and 10 were combatants. Finkelstein said four of the 10 combatants were killed from friendly fire.

Numerous independent investigations by human rights organizations contradicted the Israeli government’s claim that the majority of deaths were civilians because Palestinian militants used them as human shields, Finkelstein said.

“For every 100 Palestinians killed, one Israeli was killed. For every 400 Palestinian civilians killed, one Israeli civilian was killed,” Finkelstein said. “Does that sound like a war, or does that sound like a massacre?”

Finkelstein also disputed the claim a war had occurred because he said only one side was fighting. He cited public statements by Israeli ground soldiers who described their operations as boring because they didn’t encounter any militant ground forces. The soldiers didn’t encounter any ground forces because they said Israel had used an “insane” amount of force during air bombings, Finkelstein said.

Finkelstein said Israel instigated rocket attacks from the Gaza government, Hamas, in the days preceding the assault because Israel had intentionally failed to keep its promises after a June 2008 ceasefire agreement. Hamas agreed to stop firing rockets and mortars into Israel if Israel would gradually lift its blockade preventing aid from entering the Gaza Strip. Finkelstein said Hamas kept its promise but Israel had no intention of lifting the blockade, prompting strikes by Hamas militants.

In addition to the Gaza assault, Finkelstein challenged the Israeli government’s version of events regarding the Israeli Defense Force’s raid of a flotilla carrying aid to the Gaza Strip on May 31 that resulted in the deaths of nine passengers. The Israeli government produced a long report maintaining Israeli soldiers acted only in self-defense. Finkelstein said this was questionable because the Israeli government confiscated all images and videos of the incident and released records that only served its purposes.

Sooners for Peace in Palestine, a student organization committed to fostering understanding of the Middle East conflict, brought Finkelstein to OU.

Dalia Bayaa, vice president of Sooners for Peace in Palestine said students could benefit from hearing Finkelstein because he presents views about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that aren’t covered in mainstream media.

“I think [the conflict] needs to be more equally shown from both sides where people can judge based on both sides of the conflict,” Bayaa said.

WikiLeaks: fear of offending Muslims allowed extremists into Britain ahead of 7/7 London bombings

A fear of offending Muslims allowed extremists into Britain before the 2005 London Tube and bus bombings, a former Labour minister with close links to the intelligence services has admitted.

In WikiLeaks’ Growth, Some Control Is Lost

WikiLeaks, the Web site responsible for publicizing millions of state secrets in the last year, has tried to pick its media partners carefully. But the site has become such a large player in journalism that some of its secrets are no longer its own to control.

WikiLeaks’ latest release — files related to the detainees at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba — took place Sunday in partnership with eight news organizations in the United States and other countries, including The Washington Post and the McClatchy newspapers and The Telegraph of London. The “official” release was sped up when WikiLeaks learned that two news organizations that were collaborators with WikiLeaks in the past but were explicitly shut out this time — The New York Times and The Guardian — were preparing their own Guantánamo stories anyway, having obtained the information independently.

This resulted in a mad scramble to be first online with secrets that would never have leaked so quickly if WikiLeaks had not possessed the documents to begin with. For journalism, it was a recalibration of the traditional relationships among competitors and sources. And for WikiLeaks, it was a lesson in how hard it is to steer news coverage rather than be buffeted by it.

In its first prominent collaboration with newspapers, last July, WikiLeaks gave exclusive access to a secret archive of Afghan war logs to The Times, The Guardian in Britain, and Der Spiegel in Germany. Now, as it gradually releases 250,000 United States diplomatic cables, WikiLeaks says it has more than 50 local partners, most of them newspapers, from the Daily Taraf in Turkey to Expresso in Portugal to The Hindu in India. Some of those newspapers describe the relationship with WikiLeaks as a contract.

WikiLeaks’ intent has always been to maximize its impact, but its media strategy has changed significantly since it began in 2007, with the idea that if it posted important documents to its site — come one, come all — journalists would eagerly report the news there. Since then, it has learned the value of an “exclusive” to journalists, creating partnerships with publishers that impose a collective embargo on when the material can be published in return for privileged access to the material.

On its Twitter page, WikiLeaks suggested that it did not mind that it had lost control of its cache of secrets, saying it was pleased that its former partner publications had “added their weight to increasing our impact.”

Yochai Benkler, the co-director of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society atHarvard University, said he thought that WikiLeaks’ anti-secrecy quest was “enhanced, not undermined, by the intensification of competition to cover the documents.” The Guantánamo files, he said, confirmed what the earlier releases already suggested: that “the future of the networked Fourth Estate will involve a mixture of traditional and online models, cooperating and competing on a global scale in a productive but difficult relationship.”

In an essay this month in the British magazine New Statesman, the founder of WikiLeaks, Julian Assange, explained his reasoning. While he described WikiLeaks as “firmly in the tradition of those radical publishers who tried to lay ‘all the mysteries and secrets of government’ before the public,” he added that “for reasons of realpolitik, we have worked with some of the largest media groups.”

While the exclusive-access strategy has had obvious advantages in getting the news out, WikiLeaks faced criticism for allowing only a few news organizations to have access to the cables, said Greg Mitchell, a blogger for The Nation who published “The Age of WikiLeaks.” “Now,” he said, “it’s busting loose and other people are getting them.”

That owes partly to the falling out between Mr. Assange and The Times and The Guardian.

Bill Keller, the executive editor of The Times, said Mr. Assange seemed to sour on the newspaper after he read both a front-page profile of himself and an article about the Army intelligence analyst suspected of leaking information to WikiLeaks. The profile he deemed unflattering and the other article inadequate. He also complained to Mr. Keller that the newspaper’s Web site had not linked to the WikiLeaks site. “Where’s the respect?” he asked Mr. Keller.

Mr. Keller said Monday, “It’s been a long time since I’ve had any communication with Julian Assange.”

In essays and interviews Mr. Assange has complained that The Times had worked too closely with the United States government before publishing its material and had a “hostile attitude” toward WikiLeaks.

Similarly, Mr. Assange’s relationship with The Guardian started to fray “right at the beginning,” said David Leigh, the newspaper’s investigations editor. In late July, two days before The Guardian was to publish articles about the Afghan war logs, it learned that WikiLeaks had also shared the material with another British organization, Channel 4

“Julian had gone behind our backs because he knew that it would upset us,” Mr. Leigh said in an interview this week.

In November, WikiLeaks chose to share the diplomatic cables database with The Guardian but not The Times. When The Times and The Guardian decided to collaborate nonetheless, Mr. Leigh said Mr. Assange “burst into our editors’ office, accompanied by a lawyer, threatening that he was going to sue us.”

He did not sue, but the dissatisfaction cut both ways. Mr. Leigh said he was particularly troubled in December when Mr. Assange tried to suppress the newspaper’s coverage of the sexual assault charges against him.

By then, a competing newspaper, The Telegraph, had started holding meetings with WikiLeaks. It wanted to replace The Guardian as the group’s go-to outlet in Britain. “We were willing to ensure that their material got a worldwide hearing,” said Tony Gallagher, the editor of The Telegraph.

The Telegraph was looped in on the Guantánamo Bay file release, but The Guardian was not. Mr. Leigh called WikiLeaks’ attitude “spiteful and petty.”

WikiLeaks’ other new media partners, including The Post and McClatchy, received the Guantánamo files several weeks before WikiLeaks lifted its embargo. Unknown, at first, to the WikiLeaks partners, The Times had independently obtained the files from a source Mr. Keller would not name, and shared them with both The Guardian and NPR.

WikiLeaks itself showed some old-fashioned competitive instinct. Responding to accounts that said its partners had not been first to publish, the organization wrote: “Enough. Our first partner, The Telegraph, published the Gitmo Files 1am GMT, long before NYT or Guardian.”

Mr. Benkler, a critic of the Guantánamo Bay prison, concluded that even the “scoop the scoop” aspect of the coverage had been productive. What it amounted to, he said, were “more sources providing greater attention to what is basically continued indefensible behavior on the part of the U.S. government.”

Scientists often have a funny way of talking about religion. A respected, mainstream theologian is seriously arguing that as long as God gives the thumbs-up, it's okay to kill pretty much anybody. Why did this story not make headlines? In a recent post on his Reasonable Faith site, famed Christian apologist and debater William Lane Craig published an explanation for why the genocide and infanticide ordered by God against the Canaanites in the Old Testament was morally defensible. For God, at any rate -- and for people following God's orders. Short version: When guilty people got killed, they deserved it because they were guilty and bad... and when innocent people got killed, even when innocent babies were killed, they went to Heaven, and it was all hunky dory in the end. No, really. Here are some choice excerpts: God had morally sufficient reasons for His judgement upon Canaan, and Israel was merely the instrument of His justice, just as centuries later God would use the pagan nations of Assyria and Babylon to judge Israel. and: Moreover, if we believe, as I do, that God's grace is extended to those who die in infancy or as small children, the death of these children was actually their salvation. We are so wedded to an earthly, naturalistic perspective that we forget that those who die are happy to quit this earth for heaven's incomparable joy. Therefore, God does these children no wrong in taking their lives. and: So whom does God wrong in commanding the destruction of the Canaanites? Not the Canaanite adults, for they were corrupt and deserving of judgement. Not the children, for they inherit eternal life. I want to make something very clear before I go on: William Lane Craig is not some drooling wingnut. He's not some extremist Fred Phelps type, ranting about how God's hateful vengeance is upon us for tolerating homosexuality. He's not some itinerant street preacher, railing on college campuses about premarital holding hands. He's an extensively educated, widely published, widely read theological scholar and debater. When believers accuse atheists of ignoring sophisticated modern theology, Craig is one of the people they're talking about. And he said that as long as God gives the thumbs-up, it's okay to kill pretty much anybody. It's okay to kill bad people, because they're bad and they deserve it... and it's okay to kill good people, because they wind up in Heaven. As long as God gives the thumbs-up, it's okay to systematically wipe out entire races. As long as God gives the thumbs-up, it's okay to slaughter babies and children. Craig said -- not essentially, not as a paraphrase, but literally, in quotable words -- "the death of these children was actually their salvation." So why did this story not make headlines? Why was there not an appalled outcry from the Christian world? Why didn't Christian leaders from all sects take to the pulpits to disavow Craig, and to express their utter repugnance with his views, and to explain in no uncertain terms that their religion does not, and will not, defend the extermination of races or the slaughter of children? Because the things he said are not that unusual. Because lots of people share his views. Because these kinds of contortions are far too common in religious morality. Because all too often, religion twists even the most fundamental human morality into positions that, in any other circumstance, most people would see as repulsive, monstrous, and entirely indefensible. Step One: Admit Your Mistakes See, here's the thing. When faced with horrors in our past -- our personal history, or our human history -- non-believers don't have any need to defend them. When non-believers look at a human history full of genocide, infanticide, slavery, forced marriage, etc. etc. etc., we're entirely free to say, "Damn. That was terrible. That was some seriously screwed-up shit we did. We were wrong to do that. Let's not ever do that again." But for people who believe in a holy book, it's not that simple. When faced withhorrors in their religion's history -- horrors that their holy book defends, and even praises -- believers have to do one of two things. They have to either a) cherry-pick the bits they like and ignore the bits they don't; or b) come up with contorted rationalizations for why the most blatant, grotesque, black-and-white evil really isn't all that bad. Now, progressive and moderate believers usually go the cherry-picking route. But that requires its own contortions. Once you acknowledge that your holy books really aren't that holy, once you admit that they have moral as well as factual errors, then you have to start asking why any of it is special, why any of it should be treated any differently from any other flawed books of history or philosophy. You have to start asking why -- since your religion's holy books are just as screwed-up as every other religion's -- your religion is still somehow the right one, and all other religions are mistaken. You have to start asking how you know which parts of your holy book are right and which parts are wrong -- and how you know that people who disagree with you, who've picked the exact opposite cherries from the ones you've picked, who feel their faith in their hearts exactly as much as you do, have somehow gotten it terribly wrong. You have to start asking how you know the things you know. And to do that, and still maintain religious faith, requires its own contorted thinking, its own denial of reality, its own sticking of one's fingers in one's ears and chanting, "I can't hear you! I can't hear you!" And when you don't go the cherry-picking route? When you insist -- as Craig apparently does -- that your holy book is special and perfect, that the events and motivations in the text all took place exactly as described, and that the actions of God described in it are right and good by their very definition? You put yourself in the position of defending the indefensible. When your holy book says that God ordered his chosen people to slaughter an entire race, down to the babies and children -- and you insist that this book is special and perfect -- you put yourself in the position of defending genocide. You put yourself in the position of defending infanticide. You put yourself in the position of defending slavery, rape, forced marriage, ethnic hatred, the systematic subjugation of women, human sacrifice, and any number of moral grotesqueriesthat your holy book not only defends, but praises to the skies and offers as models of exemplary behavior. And you can't cut the Gordian knot. You can't simply say, "This is wrong. This is vile and indefensible. This kind of behavior comes from a tribal morality that humanity has evolved beyond, and we should repudiate it without reservation." Not without relinquishing your faith. And if you refuse to relinquish your faith? If you cling to the assumption that your faith, by definition, is the highest good there is, and that by definition it trumps all other moral considerations? Then you cut yourself off from your own moral compass. I've made this point before, and I'm sure I'll make it again: Religion, by its very nature as an untestable belief in undetectable beings and an unknowable afterlife, disables our reality checks. It ends the conversation. It cuts off inquiry: not only factual inquiry, but moral inquiry. Because God's law trumps human law, people who think they're obeying God can easily get cut off from their own moral instincts. And these moral contortions don't always lie in the realm of theological game-playing. They can have real-world consequences: from genocide to infanticide, from honor killings to abandoned gay children, from burned witches to battered wives to blown-up buildings. As just one example among so very many: Look at the Lafferty brothers, Mormon fundamentalists who murdered an innocent woman and her 15-month-old daughter because they thought God had commanded them to do it. At many points in theirjourney across the continent on their way to the killings, they questioned whether brutally slaughtering their brother's wife and her infant child was really the right thing to do. But they always came to the same answer: Yes. It was right. They thought God had commanded it -- and that settled the question. It ended the conversation. It stopped their moral query dead in its tracks. But don't just look at sociopathic murderers from a bonkers religious cult. That's too easy. Look at Mr. Theological Scholar himself, William Lane Craig. In this piece, Craig says that the Canaanites were evil, and deserving of genocide, because (among other things) they practiced infanticide. The very crime that God ordered the Israelites to commit. I shit you not. Quote: "By the time of their destruction, Canaanite culture was, in fact, debauched and cruel, embracing such practices as ritual prostitution and even child sacrifice." (Emphasis -- and dumbstruck bafflement -- mine.) And he says the infanticide of the Canaanite children was defensible and necessary because the Israelites needed to keep their tribal identity pure, and keep their God-given morality untainted by the Canaanite wickedness. Again, I shit you not. Again, quote: "By setting such strong, harsh dichotomies God taught Israel that any assimilation to pagan idolatry is intolerable." As if an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good god couldn't come up with a better way to teach a lesson about assimilation to pagan idolatry than murdering children. I could sit here all day and pick apart everything that's intellectually wrong with Craig's arguments. But it seems that a far more appropriate response would be, "Are you fucking kidding me? Do you hear what you're saying? Can you really not hear how grotesque, repulsive, flatly evil, totally batshit insane that sounds? Yeah, sure, if you start with your assumptions, then genocide and infanticide are morally defensible. Doesn't that tell you that there is something monstrously, ludicrously wrong with your assumptions?" If I were trying to make up a more blatant example of ethical contortionism, of morality so twisted by its need to defend the indefensible that it has blinded itself to its own contradictions and grotesqueries, I couldn't have done a better job. Craig, like so many believers before him, has made my best arguments for me. What's Sauce for the Creation Is Sauce for the Creator Now. Some people might argue that the rules of morality aren't the same for God as they are for people. They might argue that, while it would certainly be wrong for people to kill babies and eradicate entire races on their own initiative, it's not wrong for God to do it. Craig himself makes that argument in this piece. Quote: According to the version of divine command ethics which I've defended, our moral duties are constituted by the commands of a holy and loving God. Since God doesn't issue commands to Himself, He has no moral duties to fulfill. (emphasis mine) He is certainly not subject to the same moral obligations and prohibitions that we are. For example, I have no right to take an innocent life. For me to do so would be murder. But God has no such prohibition. He can give and take life as He chooses. We all recognize this when we accuse some authority who presumes to take life as "playing God." Human authorities arrogate to themselves rights which belong only to God. God is under no obligation whatsoever to extend my life for another second. If He wanted to strike me dead right now, that's His prerogative. Yeah. See, here's the problem with that. If the moral rules for God are different from the moral rules for people? If the very definitions of good and evil are different for God than they are for us? Then what does it even mean to say that God is good? If you say that what "good" means for God is totally different from what "good" means for people -- if you say that murdering infants and systematically eradicating entire races is evil for people but good for God -- then you're pretty much saying that what it means for God to be "good," and what it means for us to be "good," are such radically different concepts that the one has virtually nothing to do with the other. You have rendered the entire concept of "good and evil" meaningless. And I, for one, don't want the entire concept of good and evil to be rendered meaningless. Of course, if you're a progressive/ moderate/ non-literalist believer, you're not stuck with defending every tenet of your holy book. You can say, "No, no, God didn't command these horrors. He couldn't have. The Bible is an inspired but flawed document, and it must be mistaken here when it says this command came from God. The Israelites wanted to slaughter the Canaanites, so they went ahead with it and told themselves the order came from God. But my God is good, and my God would never tell anyone to do any such a thing." But then we're back to the cherry-picking problem: How do you know? How do you know which parts of your holy book are the ones that God meant? The Bible, and indeed most other religious texts, is loaded with instances of God commanding his followers to commit murder or worse. How do you know that God really wasn't giving those orders... but he really was giving the orders to love our neighbors and give to the poor? No two Christian sects agree on which bits of the Bible are God's true word and which bits are the "Just kidding" bits. And every sect has just as much "feeling in their heart" about their interpretation as you do. So in order to pick those cherries, you have to twist yourself into just as many contortions as the fundies do. Irony Meter Goes Off the Scale It's funny. One of the most common pieces of bigotry aimed at atheism is that it doesn't provide any basis for morality. It's widely assumed that without religion -- without moral teachings from religious traditions, and without fear of eternal punishment and desire for eternal reward -- people would behave entirely selfishly, with no concern for others. And atheists are commonly accused of moral relativism: of thinking that there are no fundamental moral principles, and that all morality can be adapted to suit the needs of the moment. But it isn't atheists who are saying, "Well, sure, genocide seems wrong... but under some circumstances, it actually makes a certain amount of sense." It isn't atheists who are saying, "Well, sure, infanticide seems wrong... but looked at in a certain light, it really isn't all that bad." It isn't atheists who are prioritizing an attachment to an ancient ideology over the clearest moral principles one can imagine: the principle that entire races ought not to be systematically exterminated, and the principle that children ought not to be slaughtered. Human beings have intrinsic compassion. We have a sense of justice. We have feelings of revulsion and rage when we see others harmed. We have a desire to help create a livable world. We have a willingness to make personal sacrifices -- sometimes great sacrifices -- to help others in need. And contrary to what Craig and many other Christians think, these moral emotions don't derive from the Bible, and don't require belief in God. They're taught by virtually every religion and every society, and atheists feel them every bit as much as believers. Humans are a social species, and these emotions and principles evolved because they help members of a social species survive and reproduce. (Other social species seem to have some or all of these moral emotions as well.) But our compassion and justice, our altruism and moral revulsion, can be twisted. They can be stunted. They can be denied, ignored, shoved to the back burner, rationalized away. They can be contorted to the point where we're saying that black is white, war is peace, and the most blatant evil is actually goodness if you squint your eyes just right. They can be contorted to the point where we're saying that genocide is okay because everyone gets what they deserve in the afterlife, and that infanticide is morally necessary to teach a lesson about the evils of murdering children. And religion is Exhibit A in how this can happen. |

No comments:

Post a Comment